Joseph was invited by the Centre for Canadian Architecture to co-curate 2021’s How To residency alongside Lev Bratishenko, CCA Curator, Public. The outcome was a digital publication featuring advice by Lev Bratishenko, Mingjia Chen, Ewa Effiom, Melanija Grozdanoska, Rebekka Hirschberg, Harriet Powell, Thea Renyong, Duncan Steele, CoCo Tin, and Joseph Zeal-Henry.

Everything produced in the digital publication was made in about fifty hours over three weeks, entirely online, resulting in eighty-seven pages of notes with over twenty-five thousand words. It was only possible because of the dedication of the participants and the generosity of the interviewees: Verena von Beckerath, Teddy Cruz, Issa Diabaté, Elsie Owusu, Amin Taha, Louis Schultz, and Dijana Vučinić. They shared their time with us and then still answered our emails at all hours.

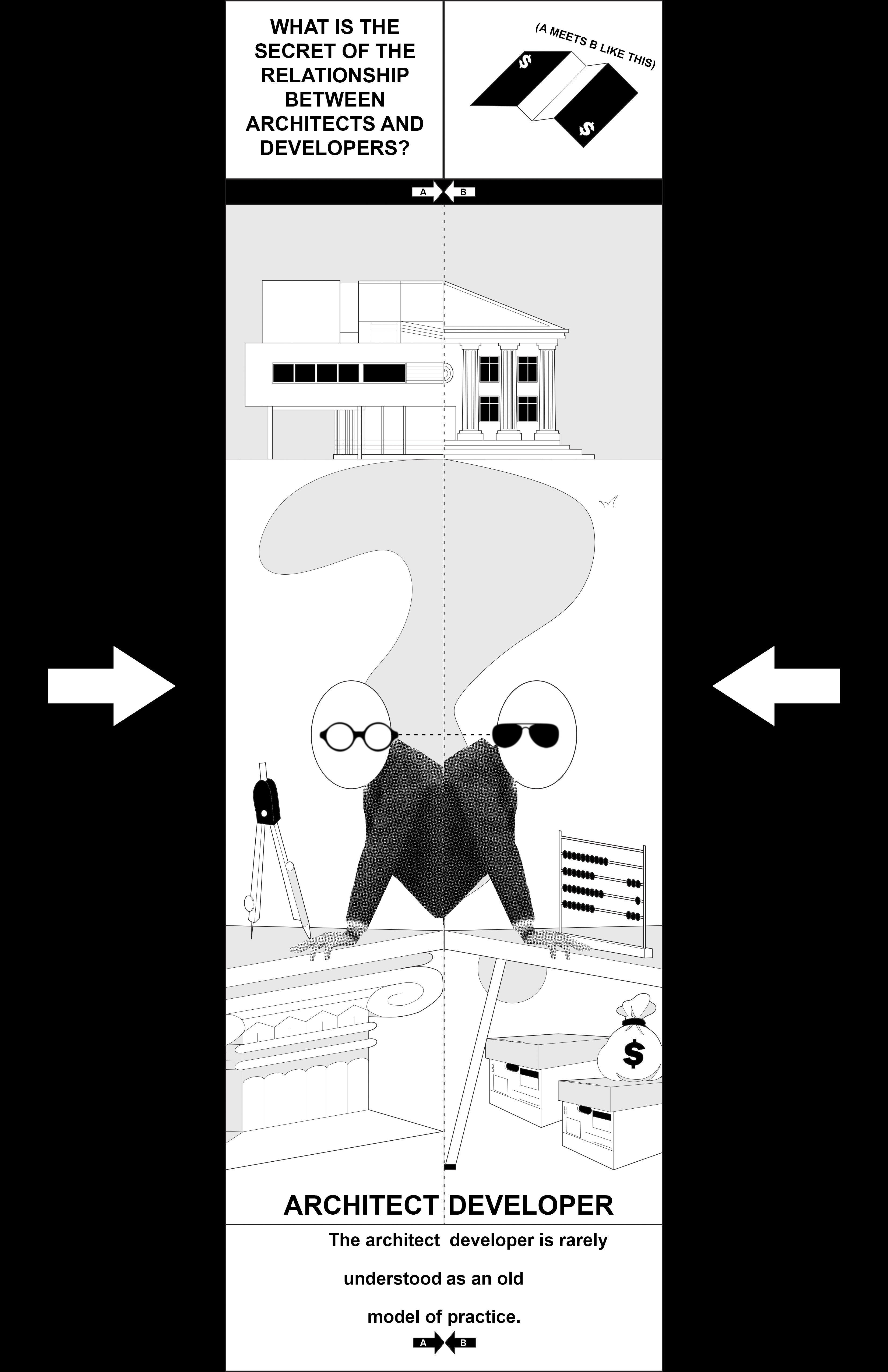

“As an architect, you might feel trapped in the role of a service provider, surrounded by crises but unable to say no to clients. That’s when the liberation of hyphenation beckons. Get your agency and confidence back with this one easy trick: Become an architect-developer and toggle your identities to best suit the situation.

Architect-developers work with investors, or for themselves, and seem to have more power to shape both buildings and the processes that produce them. And in many ways, they do. But this increased agency comes with risks. The higher you climb up the pyramid, the more you’ve got to lose. The more you invest in the system that keeps you and other architects down, the more likely it is that you become the problem. Can you hold on to your values if they don’t align with the mainstream? Must the pursuit of a more capital-intensive form of architect-developer practice double down on the inequities of access and opportunities already baked into the system? How do you manage your complicity?

A successful, lecture-circuit architect almost never talks about their relationship with money; it is implied that their ideas are so good that their finances just take care of themselves. The architect-developer, however, must defend their architectural virtue because their other values are much clearer. (Alternatively, they can keep their hyphenation a secret, and many do.) You could say that the architect-developer loses prestige because they embody a contradiction the unhyphenated architect pretends not to face. Or, optimistically and in reverse, since the unhyphenated architect claims to produce values beyond profit, a greater presence of architects in development could bring a shift in values.

Perhaps this isn’t a model of practice at all, but a space of invention”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Architect-developers work with investors, or for themselves, and seem to have more power to shape both buildings and the processes that produce them. And in many ways, they do. But this increased agency comes with risks. The higher you climb up the pyramid, the more you’ve got to lose. The more you invest in the system that keeps you and other architects down, the more likely it is that you become the problem. Can you hold on to your values if they don’t align with the mainstream? Must the pursuit of a more capital-intensive form of architect-developer practice double down on the inequities of access and opportunities already baked into the system? How do you manage your complicity?

A successful, lecture-circuit architect almost never talks about their relationship with money; it is implied that their ideas are so good that their finances just take care of themselves. The architect-developer, however, must defend their architectural virtue because their other values are much clearer. (Alternatively, they can keep their hyphenation a secret, and many do.) You could say that the architect-developer loses prestige because they embody a contradiction the unhyphenated architect pretends not to face. Or, optimistically and in reverse, since the unhyphenated architect claims to produce values beyond profit, a greater presence of architects in development could bring a shift in values.

Perhaps this isn’t a model of practice at all, but a space of invention”